One Man’s Journey from Facing a Stroke to Splitting Wood

There are many stories about people living with debilitative conditions who might find their lives changed dramatically by the introduction of new treatments, medications or prosthetics, but there are also those whose health conditions themselves are more immediate and/or severe. While a person managing diabetes might benefit gradually from a new medication, a person with a more acute condition might go undiagnosed for years and then suddenly find themselves facing a life-threatening situation that requires immediate, consequential decisions.

Such was the case with Donald Skroski, 65, of Whately, who was about to get up and go home from his routine appointment with Timothy Parsons, MD, his primary care physician, when Parsons noticed something that didn’t sound right when he placed a stethoscope to his neck. The sound was odd enough that his doctor ordered a follow-up ultrasound, and it was determined that Skroski had substantial blockage in both of his carotid arteries, a condition known as carotid artery stenosis. Caused by a buildup of cholesterol plaque, the condition can be a particularly dangerous one in that often it presents no obvious symptoms until a piece of plaque breaks loose, travels a short distance right up to the brain and causes a stroke.

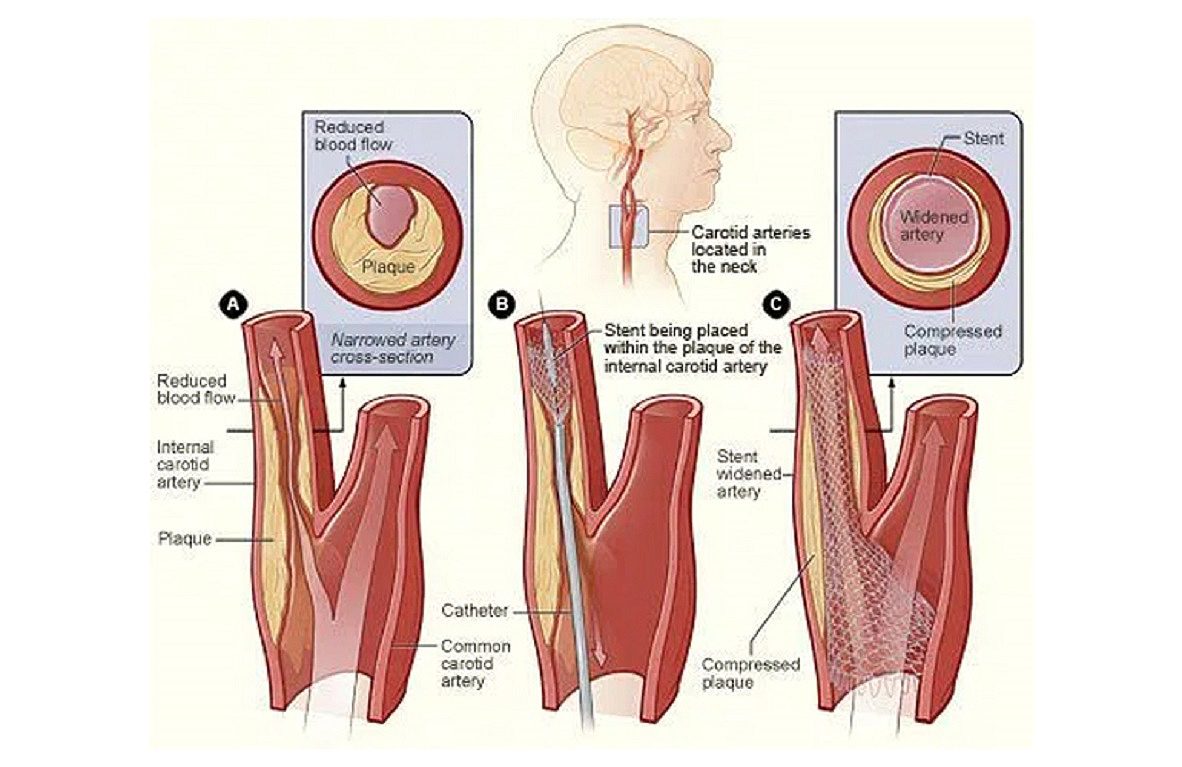

Parsons referred Skroski to James Arcoleo, DO, a specialist with Cooley Dickinson Medical Group’s Hampshire Cardiovascular Associates known for his extensive work with carotid, coronary and peripheral interventions, and other manifestations of vascular disease. Arcoleo offered either surgery or implanting arterial stents, and discussed the advantages and disadvantages of each. Implanting carotid stents is a procedure that he performs regularly at Massachusetts General Hospital’s Corrigan Minehan Heart Center, of which Cooley-Dickinson Health Care is an affiliate institution.

The process, which involves placing a small, expandable tube inside a narrowed artery and widening it by inflating a balloon, opens up arteries to increase critical blood flow, and is usually performed in conjunction with blood-thinning medication to protect against pieces of plaque potentially breaking free.

Skroski decided to go ahead with the procedure in the spring of 2016, and by June he was in for his first stent. His wife drove him to Boston for an overnight stay, and he says the recovery time wasn’t so bad.

“They don’t let you do any heavy lifting for a while and you can’t drive for a week or so,” he recalls.

After only a couple of months, he went back to have another carotid stent put in on the other side. He remembers lying on the operating table for a while after the procedure—usually patients are observed for some hours afterward to make sure that they don’t have a stroke—and talking to Arcoleo through a haze of anesthesia.

“’Thank you’, I said, ‘You did a good job.’ And Dr. Arcoleo turns to me with a smile and says ‘I couldn’t have done it without you.’ He’s great. So were Dr. Parsons and everybody at Mass General—I’m a lucky guy,” Skroski acknowledges. “I could’ve stroked out at any time. Even if this didn’t kill me I could’ve wound up really messed up for life, put in a nursing home, you know.”

Now Skroski’s life is back to normal: Cutting, splitting and stacking his family’s firewood, and being there to stay involved in the lives of his five grandchildren. He still has to take meds, but his risk of sudden death has been vastly reduced, and the stents allow him to go about living life not just as well as before procedures but at an improved level.

“You know, I didn’t really get any of what they say are typical side effects,” he says. “Swollen calves and stuff… and I feel like I have a lot more energy.” The feeling is not an unusual one after stenting procedures, since one of the beneficial effects tends to be considerably improved blood flow and a greater supply of oxygen to the brain, heart and muscles—all good things for Skroski, who stays active. “I’m not a couch potato,” he says with an air of confidence that he’s acquired from living with the stents for a while. “I can do anything I want.”

Asked how he felt the procedures went overall, Skroski responds very positively about the entire process from diagnosis through surgery and recovery.

“If someone asked me if I would do it again,” he ponders, “Yeah, I would. Everything went like clockwork.”

PHOTO: CAROTID STENT – NIH PHOTO